BACKGROUND

As the opioid crisis has steadily worsened, many county, state, municipal, and tribal governments have sought to hold manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers of pharmaceutical opioids liable for their role in the crisis. The primary method these governments are using to pursue litigation against companies in the pharmaceutical opioids industry is through multidistrict litigation (MDL). Like class actions, MDLs are a procedural device for dealing with mass litigation. There are, however, important differences. Unlike class actions, MDL plaintiffs can have very different damages and, in the event that the parties do not reach a settlement or the judge does not dismiss the case, the individual plaintiffs’ case can be remanded back to the original trial court for resolution. However, little research has been conducted on MDL cases and on opioid litigation in particular.

For this project, Policy Lab partnered with the RAND Corporation’s Institute for Civil Justice in order to study the National Prescription Opiate Litigation (MDL number 2804) and how it relates to past MDL cases. This research has four main areas of focus. The first concerns the geographic distribution of the plaintiffs, and the relationship these plaintiffs have with different demographic variables. The operative question here is what variables are correlated with whether a county has decided to sue. The second area of focus is to track whether prominent attorneys in past MDL cases retain their prominence in current opioid litigation, or if different attorneys are taking the lead in litigation, as the causes of action have grown more diverse. The third involves tracing the evolution of the causes of action filed in legal complaints over time. In earlier litigation of opioid cases, the traditional causes of actions proved difficult for plaintiffs to prove. As a result, the causes of action in the more recent opioid MDL have evolved considerably, invoking more complicated claims such as civil conspiracy and racketeering. Policy Lab and RAND seek to track this evolution and determine what new causes of action are the most prominent. The final area of focus lies in developing an appropriate classification system for the plaintiffs and defendants to gain a better look at the parties involved in the litigation.

GEOGRAPHIC VISUALIZATIONS

Once the preliminary county identification was finished, Policy Lab could begin work on the project itself. The first portion of the opioid multidistrict litigation project focused on data compilation and constructing maps and scatter plots using Tableau. The aim of the maps was to visualize both the geographic dispersion of county plaintiffs over time, as well as any relationship between different demographic characteristics and whether or not a county decided to sue. The aim of the scatter plots was to show the relationship between the severity of the opioid crisis and other different demographic factors. Each scatter plot contained two trendlines, one for counties that decided to sue, and one for counties that decided not to sue, in order to demonstrate any significant divergences between those two groups. The maps and scatter plots contained data from a variety of sources, including the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bowling

Green State University, the Center for Disease Control, and the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

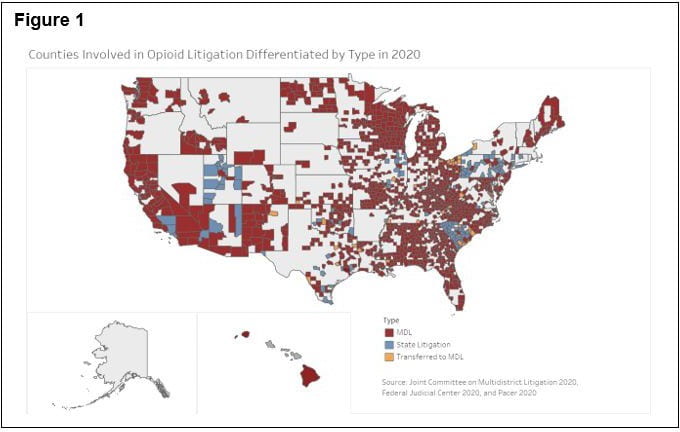

Figures 1 and 2 display two of the maps, giving examples of a map demonstrating plaintiff dispersion, and a map demonstrating demographic variance between counties.

Taken as a whole, the plaintiff dispersion maps Policy Lab created illustrate both the rapid growth in the number of counties involved in the opioid multidistrict litigation case as well as that more counties are opting to join the MDL instead of pursuing litigation in state courts. The demographic maps tend to demonstrate that areas that are poorer, less educated, or have high rates of divorce, tend to suffer more acutely from the opioid crisis. The most surprising finding from the scatterplots is that for counties involved in opioid litigation, there appears to be a positive correlation between the severity of the opioid crisis and median household income. One possible explanation for this is that counties with a higher median household income have a greater capacity to pursue litigation.

NETWORK ANALYSIS

The second portion of the opioid project involved examining the prominence of particular attorneys in multidistrict litigation over time. This portion of the project was inspired by a paper written by Elizabeth Burch, a law professor at the University of Georgia, entitled “Repeat Players in Multidistrict Litigation: The Social Network.1” Burch’s research demonstrated an intuitive fact: that attorneys who have been involved with, and successful at, multidistrict litigation in the past will continue to be involved with multidistrict litigation cases in the present. However, Policy Lab had reason to suspect that this opioid MDL might be different. As opioid litigation has evolved, the causes of action being brought became more diverse over time.

Assuming that an attorney who brought one of these newer causes of action was marginal compared to the repeat players that Burch referred to, could this hypothetical attorney be a more prominent player attorney in this MDL than the repeat players?

In order to test and visualize this, Policy Lab used a network analysis. Using party-level data from the opioid MDL and 73 prior product liability MDLs, Policy Lab created a network of all plaintiff and defense attorneys involved in these MDL cases. Each lawyer serves as an individual node connected to others through shared participation in the same MDL.

This network finds the central, repeat players within the ongoing litigation, particularly those working on the opioid MDL. We are currently exploring various means of assessing centrality, including degree, path, and eigenvalue centrality. This information will be important in discovering the extent to which repeat attorneys may be able to use their position to change the “rules of the game,” as well as if it is possible for a marginal attorney to change the rules.

Work on this portion of the project is only partially complete and will continue into the fall. However, the network analysis preliminarily found that the Opioid MDL is more connected than average products liability MDL, with over half of plaintiff lawyers appearing in more than one case, and almost 80% of defense lawyers appearing in more than one case. Additionally, roughly double the percentage of lawyers represented more than 1,000 clients compared to products liability MDLs at large.

COMPLAINTS ANALYSIS

While working on other projects, the Policy Lab RAs worked to compile data on the causes of action and the prayers for relief in the complaints for every individual case within the opioid MDL. The goal of this portion of the project was to analyze trends in the causes of action and prayers for relief named in the complaints. With a sample of roughly 500 cases, Policy Lab has been able to compare how single Nature of Suit codes assigned by the Administrative Office of the Courts align with multiple causes of action, how causes of action evolved between cases filed earlier versus later on in the MDL, and how certain causes of action are commonly paired together. By reviewing prior literature on federal causes of action and nature of suit codes, Policy Lab has ultimately been able to compare observations from our sample of cases from the opioid MDL to general observations about the salience of these codes and causes of action in mass civil litigation.

The results from this analysis indicates that the top causes of action were negligence, public nuisance, racketeering, and fraud, while the top prayer for relief sought was attorneys’ fees. Racketeering dominated the nature of suit codes, even as it grew less prominent over time as a cause of action. The most common pairing of different causes of action was negligence and public nuisance, while it was uncommon for fraud and racketeering to appear together.

Compared with prior literature on past MDL cases, this opioid case shows a great diversity in the causes of action alleged, and the fact that racketeering dominates the nature of suit codes is quite unusual.

PRODUCT, PLAINTIFF, and DEFENDANT CLASSIFICATION

The final aspect of the opioid litigation project was to create three different classification systems, one for the products involved in past multidistrict litigation cases, one for the plaintiffs in the opioid MDL, and one for the defendants in the opioid MDL. The purpose of this portion of the project is twofold, both related to the fact that no research has yet been conducted on this particular round of opioid litigation. For the products in past MDLs, developing a classification system will enable Policy Lab to compare the opioid MDL to past MDL cases. It is unclear if the current round of opioid litigation has more in common with past asbestos litigation, past tobacco litigation, or if it falls in line with past MDL cases. Examining the products involved in past MDL cases is an important first step in this process. For the plaintiffs and defendants, developing classification systems will allow Policy Lab and RAND to look at such factors as the types of governments or organizations that are the most likely to bring legal action, as well as the types of defendants most likely to be on the receiving end of litigation.

The simplest classification system to produce was for past products. The starting point of the analysis is a large subset of MDL cases complied by Dr. Elizabeth Burch. Dr. Burch’s datais based on all MDL cases that included a judicially appointed lead plaintiff and defense lawyers in all products-liability and sales-practices cases pending as of 2013. An analysis of this list revealed that the majority of MDL cases were related to either medical devices or pharmaceuticals. Other larger categories included MDLs related to vehicles and MDLs that related to products used in infrastructure and construction. In a further analysis of the two largest categories, medical devices and pharmaceutical drugs, Policy Lab found that the types of drugs targeted in these MDLs varied greatly in use, from medication used to treat gastric reflux to ‘diet drugs’ prescribed to aid weight loss. There was no clear trend in the types of drugs targeted in MDL cases. However, in the medical devices category there was one main underlying theme. Eleven of the MDL cases were against specific medical products involved in the production of products used in hip replacements, pelvic replacements and knee replacements.

The plaintiff and defendant classifications were more difficult and time-consuming to develop owing to the large number of each. The categories that the plaintiffs were initially sorted into included: hospitals, counties, police units, individual cities, tribes, unions, coroners and states. The plaintiff’s home state was also indicated. Policy Lab found that the three states with the highest number of identified plaintiffs were Alabama, Georgia and Kentucky. As expected, plaintiffs predominantly consist of counties and cities. Apart from this, the largest plaintiff categories were hospitals and tribes, being 7% and 4% of the plaintiffs respectively.

While Policy Lab had a list of defendants, they were not always easy to classify. This is because many defendants in the opioid litigation MDL do not fall into the neat categories of manufacturers, distributors, or retailers. Many companies participate in both or all three. To resolve this, Policy Lab made use of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). These codes offered a practical way to classify defendants, provide a more holistic picture of the defendants involved in the litigation, and can be applied to compare defendants in the opioid litigation to those in previous public health litigation. To implement this system, Policy Lab revised the list of defendants and removed individuals (e.g., Jonathan Sackler and physicians), states, and counties. We then refined the remaining defendants such that each company would be included once. This is because the naming convention for one particular company was not always standardized. The results of this classification system indicated that, even when accounting for companies that operate across multiple industries, the three most prevalent were companies who operated exclusively as pharmaceutical retailers, pharmaceutical manufacturer, and pharmaceutical distributors, accounting for 25%, 19%, and 12% of the all defendants respectively.

1 Elizabeth Chamblee Burch and Margaret S. Williams, Repeat Players in Multidistrict Litigation: The Social Network, 102 Cornell Law Review 1445 (2017) https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol102/iss6/2.

Bibliography

Burch, Elizabeth Chamblee. Mass Tort Deals: Backroom Bargaining in Multidistrict Litigation. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Project Partner: RAND Corporation

Faculty: Eric Helland, Co-Director

Research Assistants: Harrison Hosking, Benjamin McAnally, Emily McElroy, Scott Mowat, and Hallie Spear

Lab Managers: James Dail and Melanie Wolfe